First Flowering

Astronomers and telescope operators have a term, “first light,” that is kind of what it sounds like: the first time that light passes through a new telescope and makes an image.1 There ought to be something like this for horticulture and gardening. I was happy to see flowers emerging, for the first time, from seeds I started stratifying two seasons ago, in late fall of 2023.

These are Calico Beardtongue (Penstemon Calycosus)

The term is supposed to be limited to an image taken from a new telescope, but amateurs will often extend it to mean the first use of a new telescope of any kind, including looking through an eyepiece. ↩︎

The Power Mountain

Late this past weekend I took a look at HBO’s new film Mountainhead. It’s gotten a lot of mainstream attention in the last few weeks, including about the $65 million house where the movie is set.1 Mostly, I found the movie to be a quite literal and unlikeable presentation of a few widely circulated criticisms of the tech industry. Like Succession, also written and directed by Jesse Armstrong, it seems to draw a lot of its appeal from the voyeuristic curiosity of its audience. Mountainhead watchers must wonder about what type of house you vacation at when you are young-ish and among the richest people in the world. What does entertainment, friendship, work-play look like at this level?

This is one of those films that only makes sense if it comes with a claim to show “how it really is.” And yet, given the exclusivity of the subject matter, how would the audience know if the movie had gotten it right? One answer is that the film brings an obscure, elite situation down to the level of gossip–to the eminently comprehensible. These men, who claim to rule by means of their extraordinary talents and intelligence, must be disarmed, so that their fate unspools itself only through their basic qualities (honesty, courage, loyalty, ruthlessnes etc.). We may not be able to judge if the opulent setting is credible, but we can judge a character that is confronted with a situation.

What is distinctive about the setting of this movie is that it strips these men of their power. To buy this place at the top of the mountain and associate with one another, they had to fight to the top of the metaphorical pinnacle, conquering or creating entire industries. But all of the planes and motorcades and massive corporate armies that they command are removed from the situation. It’s a “poker weekend,” time off the clock, a chance to revel in ordinary time. And the film shows us leaders whose discomfort with power is almost paradoxical. What they seem to want is supremacy over one another: to be richer, more successful than the next person in the treehouse.2

Read more →The Allure of Withdrawal

Withdrawal and the so-called “ivory tower:” this is the constant temptation of any thinking person–especially those intellectuals who want to produce something that is likely to last.

Reading Lionel Gossman’s Basel in the Age of Burckhardt: A Study in Unseasonable Ideas, he has a case study on the Swiss scholar Johann J. Bachofen. Born in 1815, Bachofen was the intellectually talented scion of a wealthy family, appointed at a young age to a professor’s chair at the University of Basel, with high expectations that he would ascend to political life and the city’s governing elite. But objections to his appointment led to a minor public scandal; the inexperienced, sensitive Bachofen was more than rich enough to withdraw from formal employment entirely, which he largely did for the remainder of his 71-year life. While he would make a name for himself in posterity with his intellectual work (Mother Right), which he pursued without institutional restraint, the upheavals and revolutions across 19th-century Europe that he witnessed with increasingly conservative horror led him to an attitude of withdrawal from the world. Gossman describes it:

In the face of the collapse of traditional societies and traditional values, the only reasonable policy was to withdraw, cultivate those things that would enrich one’s own inner being and that might be shared with a few other individuals similarly inclined, and thus wait out the coming crisis, as it were, in order that beyond it, when humanity had come to it senses again, the torch of true learning and wisdom might be handed on. For though Bachofen described himself as a “pessimist,” he did not believe–any more than Burckhardt did–that the present age was the last word on human history. “The old world of Europe lies on a sickbed from which it an expect no lasting recovery,” he wrote to Meyer-Ochsner, but this did not signify the end of history, only the destruction of that which had to be sacrificed so that the history of mankind could take on a new turn. Sickness and death were the prelude to regeneration. Whatever the fate of the established states, therefore, “at the individual level, much that is good can be salvaged, much that is worthwhile can be newly created.” So, too, at the local level: “The best seek a sphere of activity in the concerns of their municipality. From there they hope to win back later a part of the ground that has been lost. My past experience and my studies indicate that my province should be that of magistrate and judge.” All the effort and energy expended on politics and the state is now best directed toward the improvement of individual lives, for it is individuals who will transmit what can be salvaged of the old culture, not states. (132)

Read more →

Winged Fruits

Found: the length of a maple seedling in the early stages of germination, with all of its parts (the wing, the seed, the seedling itself, the start of a root system) well-preserved and still connected.

A gallery of maple (Acer) samaras (winged fruits) in the USDA Seeds of Woody Plants in the United States forest service guide, 1974:

Soil Series

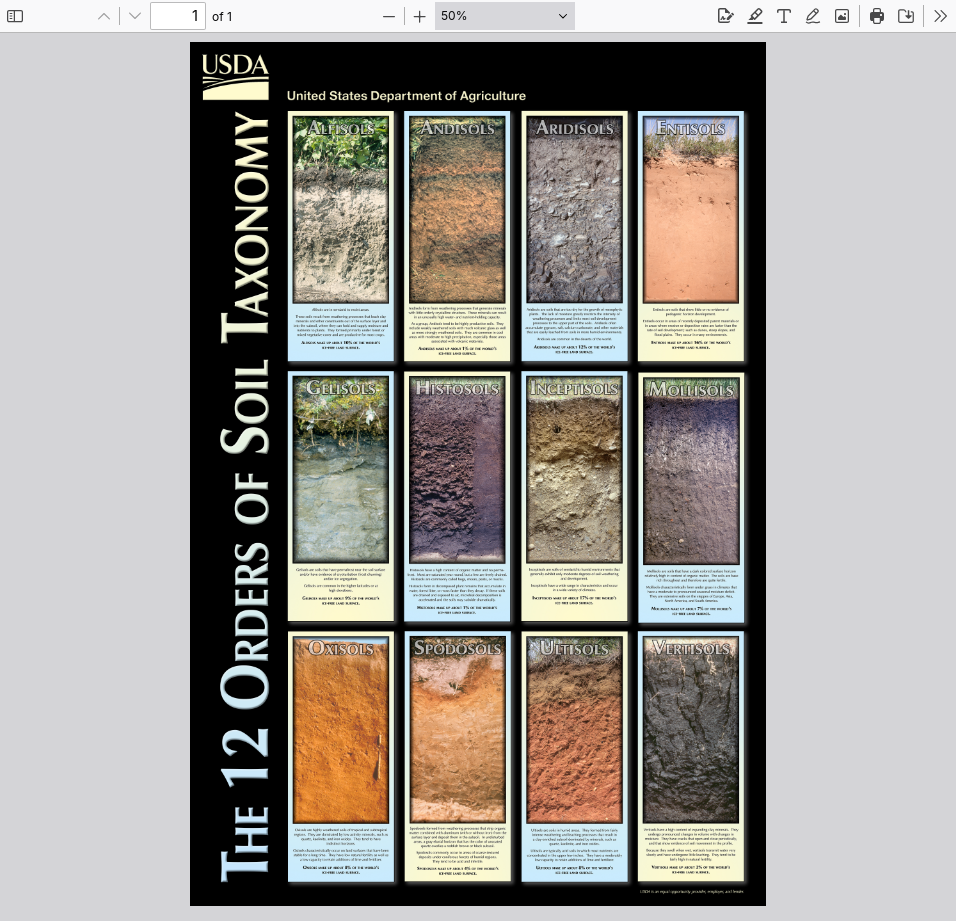

When does a system of classification limit the imagination, and when is it liberating? Today in the course of reading about something else I stumbled upon the USDA classification system for soils, helpfully illustrated in a great poster:

As it turns out, the US Department of Agriculture maintains an entire taxonomy of soil types, not unlike the Linnean hierarchy for life. The soil version includes orders, groups, families, and finally the series. At the lowest level there are many, many series–perhaps not as many as there are living species, but still, for the majority of the population that has moved away from agricultural occupations, a staggering number of soils. From Wikipedia:

About 4,500 soil families are recognised in the United States…A family may contain several soil series which describe the physical location using the name of a prominent physical feature such as a river or town near where the soil sample was taken. An example would be Merrimac for the Merrimack River in New Hampshire. More than 14,000 soil series are recognised in the United States. This permits very specific descriptions of soils.

Take a look at the start to USDA’s description of the “San Joaquin” series:

The San Joaquin series consists of moderately deep to a duripan, well and moderately well drained soils that formed in alluvium derived from mixed but dominantly granitic rock sources. They are on undulating low terraces with slopes of 0 to 9 percent. The mean annual precipitation is about 15 inches and the mean annual temperature is about 61 degrees F.

Read more →

Brighton Park Chicago

From the Chicago Park District:

The site consists of multiple parcels grouped into one, that previously housed a number of factories and processing facilities. These included Chicago Tube & Iron, Wilson Steel & Iron, and the former “World’s Famous Chocolate” facility. As these parcels housed industrial uses, environmental remediation was necessary to render the entire site fit for public park use. Remediation efforts began in 2019 and were completed a year later.

Southbank Riverwalk

By accident, walking at lunchtime yesterday, I walked far enough south from my office to come upon this new rivewalk path, the “Southbank Riverwalk,” that follows the South Branch of the Chicago river for a few hundred yards. When I walked it, in the middle of the day on a weekday, it was almost as empty as an architectural concept drawing.

Cities spend a long time trying to push nature away, to turn the earth into abstract space fit for development. Few cities make this more obvious than Chicago, the most grid-like metropolitan area in the world. But when a city reaches a certain point in its development, the effort reverses; it becomes pleasing to bring nature back in.

The boardwalk lets its traveller float across nature; the walker gets close to the trees, bushes and ground, without scraping up against the surfaces of plant or earth. The boardwalk is the long, straight line that maintains the geometric and regular built world.

Indeed the nature walk in the city might be at its best when it uses natural elements, like trees, to frame all the familiar monuments.

A New Lack of Information

I was sitting at my computer this evening googling about a half-formed question, something like “how much of the current U.S. and world economy is made up of goods versus services, how is a ‘good’ defined, and is there any sign that the U.S. service economy is losing ground in the post-Covid era?”–when it occurred to me (or rather, occured to me all over again) that all of the sources I found online were not very good. Now, if I brought a little prior knowledge and intentional effort the question, if I searched for respectable public institutions–like the Fed–that put their data online, I would surely find a start to these questions. But these are things that one would have to know. For the average person, you want to know the answer to something non-commercial, you just start typing questions as they occur to you, and you will probably give up clueless because online search these days is remarkably bad. It’s not that all of my questions had been targeted by low-quality content farm sites, but rather that a lot of the more mainstream sites that came up first–like a link to a LinkedIn post, or a Forbes article, or a Harvard Business Review blurb– were all generalist filler. And on down for several pages, with the occasional news article from a few years ago or a general Wikipedia topic ("Service economy") thrown in. Search is not very good in large part because the sites that count as “average” are mediocre at best.

Read more →Dayswork

I’ve been reading Jennifer Habel’s and Chris Bachelder’s book Dayswork. Actually, dipping into it, then falling away; losing interest for a while. then coming back. The episodic approach to reading works quite well for a book, written during the Covid pandemic, in an aphoristic format. Many of its passages could be tweets. The book has the feel of something written in a makeshift desk–maybe from a closet–when the writer is supposed to be doing something else (I don’t know, exactly, what the writing process was for Dayswork). But it also reads like a product of the distracted modern condition of reading. Judging by how active even many serious writers have been on X/Twitter over the past decade, I suspect that distraction is also the predominant condition of writing today.1

The waves of “Melville revival” that brought him into the American canon have always had an obsessive devotion to the historical Melville; the quotidian, real person: adventurous, flawed, idiosyncratic. Dayswork contributes to the cult of the author. While the book does use Melville’s literary work as an anchor, it spends just as much time pecking at the minutia of the author’s life. The book spends a lot of time introspecting about other figures connected to Melville, some of them people he knew (his wife Lizze Shaw, daughters Elizabeth and Frances) and others later interpreters or admirers, like Elizabeth Hardiwick. One of the most frequently mentioned figures, “The Biographer,” is still commenting on Melville as of early 2024. The Biographer remains unnamed until the book’s end. He is Herschel Parker, a retired English professor and Melville scholar from the University of Delaware. Author of not just a Melville biography, but of a Melville meta-biography. And, most relevant to Dayswork, he also maintains an active blog in which–guess who?–Melville comes up a lot.

Read more →